This week, the Foundation was lucky to receive a visit from Anjil Adhikari, Wash and Innovation Advisor for Oxfam in Nepal, and get an update on Oxfam’s WASH work in the country.

Oxfam is exploring how a financially viable management model could work to ensure sustained safe water access for communities long after project’s end. A professionalised public Water Service Provider could engage local private sector actors to better financially manage and technically operate and maintain the water system if communities were to pay a reasonable tariff to cover ongoing costs.

Wanted: water scheme sustainability

Sustainability of public water schemes is a critical issue in Nepal. Studies by the Nepalese government (2014) and the World Bank (2017) showed that a whopping 75 % of government water supply schemes were failing within less than two years ofimplementation.

“Every year, the government was spending huge amounts of money on water infrastructure, but the systems were breaking constantly, which affected the financial sustainability and the public trust in the scheme”, explains Anjil Adhikari.

Oxfam Nepal has been investigating the case and developed a new management model which they are now testing. Two water schemes funded by the Poul Due Jensen Foundation will be the testing ground of what is hoped to be a game-changing new approach.

Anjil Adhikari and his team found that 8 out of 10 schemes experienced pump breakdown or pipe leakages within the first two years. The schemes would spend a lot of their income repairing and replacing pumps and parts, which meant that the schemes were not able to save up as much as planned.

Pump burnout and poor piping

In general, the communities blamed the pump or the operator for the breakdown. But surprisingly, the reason the inferior quality pumps were often breaking down was not what we may have suspected:

“We asked the pump repairing companies what caused the breakdown, and they told us that 85 % of the pumps had burned out because of voltage fluctuation in grid power!”, Anjil Adhikari says.

So, the problem was not in the borehole, but rather that the electrical installation could not handle the instability of the grid power without any protection. Ideally, the system should be able to handle it, but there was no tradition of looking at the real problem. They would just repair the pump and wait for it to break down again.

“A key learning from this exercise was that we need to consider this problem in the way we design the system and the maintenance model”, explains Anjil Adhikari.

When it came to the piping, they found that the traditional approach of asking the community to buy into the project by laying the piping was in fact a bad investment, because they simply (and understandably) did not do it correctly, resulting in leakages and increased need for repairs.

Market-oriented approach

Although people are very poor in the area we work in (learn more here), Oxfam knew it needed an ambitious public-private partnership approach which could potentially overcome the problems of the community-managed water schemes.

“In our new model, we look at the beneficiaries as customers that we need to convince to buy the service before we start constructing it. When they sign up, we give them all the fittings for the household tap and instructions on how to build it. We need around 60 % signup before we start construction, so we have to market the solution and convince them why they should buy into it,” Anjil Adhikari says.

Tariffs must be affordable for all families – defined as no more than 5% of household income. To ensure that even the poorest households can afford water, a smart tariff structure would include subsidies for the most marginalised families – this will always be an essential consideration to ensure we leave no one behind.

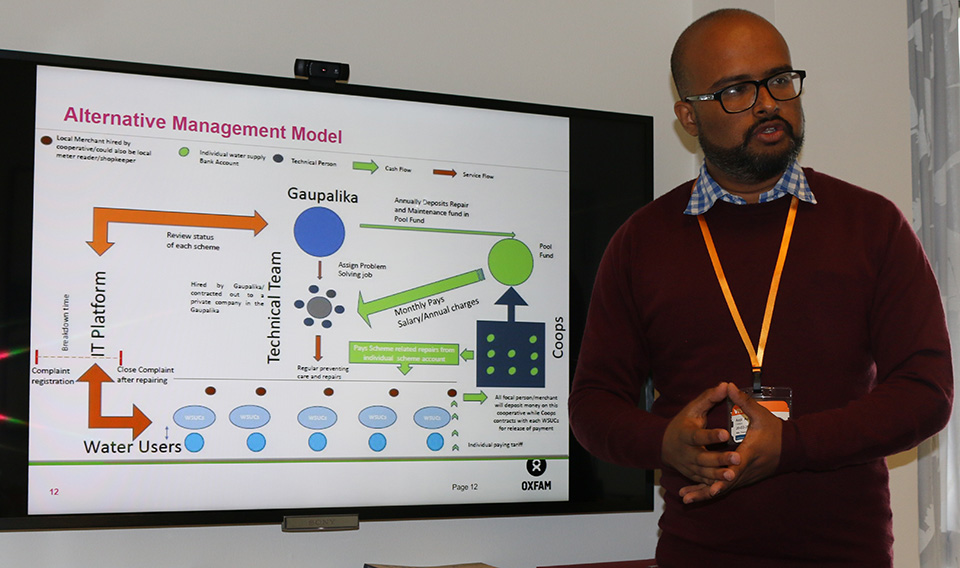

Anjil Adhikari, Wash and Innovation Advisor in Oxfam in Nepal, presents the new management model to the Foundation. Photo: Poul Due Jensen Foundation

The county (Gaupalika) would be responsible for contracting out service, maintenance and repair to a professional service provider and collecting fees from the customers via a co-op structure. The service provider would then be responsible for looking after several water schemes in the same area, which of course requires a critical mass. That’s why the two schemes we are building together are crucial to test the tariffs and billing models on the customers and convince the politicians that the model works and is replicable. But they are not enough, so Anjil Adhikari and his team are working hard to add more schemes to the pool of schemes:

“In Terai, we would need at least 16 schemes to have enough business for this service company. We only have two, so we need to add existing schemes, so we are exploring how we can make fixes and repairs to be able to include them in this management model.”

Oxfam has asked the local Gaupalika to do the initial investment in professional pipe-laying in order to avoid repeating the problems of the past. The new model should ensure that, over time, the schemes become profitable instead of loss-making, benefiting everyone.

For this model it is key that the Water Service Provider is accountable to the community for the services it provides, and Water User Committees (WUC) comprised of local people will also be established to represent the voice of the water users (tariff payers) in the community. This would replace the current model wherein voluntary community groups are directly responsible for operation and maintenance of the systems, despite their understandable lack of technical capacity and poor accountability. This new model allows communities to take ownership of the system through paying what they can to keep systems operational, and ensures they know their rights to safe water access so they can hold their water providers to account.

Overcoming trust issues

Due to their long experience of failures and false promises around previous attempts at water schemes, it is proving difficult to convince the consumers that this new model will actually work. But Oxfam has been communicating through all possible channels such as door-to door contact, mass meetings, public scientific demonstration of improved water quality, delivering messages via community leader and politicians, but also showing the customers that there is progress and that their investment will pay off. Oxfam has worked in Nepal since the early 1980s and its local staff and local partners are deeply embedded in local communities, incredibly important as we build relationships and are guided by residents’ needs and concerns.

“It takes time to absorb it. We need to show them what they get for their money,” says Anjil Adhikari.